The Gray family set off for Australia as assisted immigrants on the ‘Thomas Arbuthnot’ leaving London 22 Sept 1848 and Plymouth 3 Oct 1848. George Gray was 31 years of age (Ann was 27yrs) and on their records they listed their religion as ‘Bible Christian’ (Methodist).

Assistant Immigrants to New South Wales

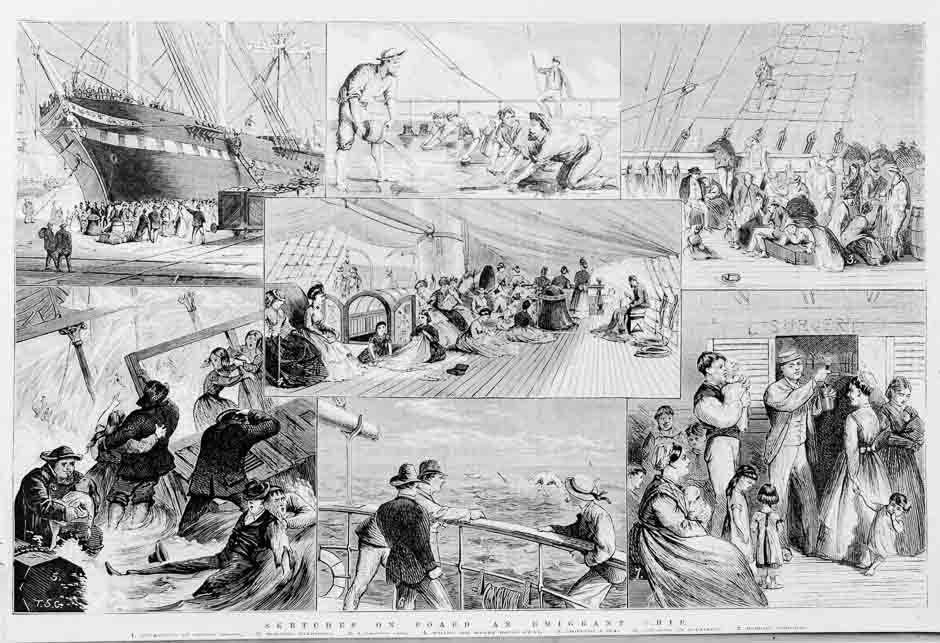

Sketches on board an emigrant ship, 1875. Thomas Cousins, artist, and Samuel Calvert (1828-19 13), engraver.

Illustrated Australia news for home reading, 24 March 1875.

Montage of sketches depicting life on board an immigrant ship showing emigrants embarking at the London docks, scrubbing the decks, watching a passing ship, dealing with heavy seas, catching an albatross, and queuing at the surgery.

“Most vessels sailed non-stop to Australia from the mid-1840s. In the 1850s time saving, record-seeking captains favoured the newly discovered Great Circle route. Emigrants encountered perilous seas, freezing conditions, and great discomfort when ships sailed this extreme route.

To counter the tendency of captains to compete for the fastest sailing time via the high southern latitudes where Antarctic pack ice was often seen, the Emigration Commissioners introduced a ‘modified’ or ‘composite’ Great Circle route. Between 1 April and 1 October (the southern hemisphere’s autumn and winter), ships were forbidden to sail higher than 47 degrees south; between 2 October and 31 March, no higher than 53 degrees south. (Map drawn by Margaret Hooper).” 1

Australia in the 1840’s had a labour shortage, those trying to run farms and business were crying out for help. Many emigrants like George and Ann Gray put themselves forward for an assisted passage to Australia as an opportunity for a new life and a way to improve their circumstances. Given George’s rime in the debtors prison in 1844 the chance at a new life in the colony with the chance to start again might perhaps have been reason enough to undertake the venture. The records of George and Ann are within the Assisted Immigrants in the NSW State Archives – INX-9-164792.

In order to be considered the prospective immigrants needed to qualify for the assisted immigrant program requiring them to be of a certain age, in good health, have smaller families (those with more than 3 or 4 children were not considered due to the difficulties to bring large families out to Australia presented).

“As well as a character reference, a certificate of health from a local practitioner – often the poor law medical officer attached to their parish – was required on their application form. To ascertain their fitness for the voyage, their vessel’s surgeon superintendent again examined them at the emigrant depot before departure. He was also expected to ensure that they did not harbour any observable deformities or infectious diseases. In these respects, the least fit candidates were rejected before departure.” 2

Occupations and trades that were valued included; agricultural labourers, dairymaids, tradesmen, shepherds, farmers and servants to work in both towns and rural settings. Back in England these occupations were amongst the lowest paid in the British economy and meant that many emigrants who travelled on an assisted passage were amongst the poorest and most under-nourished people in Britain.

“Like shipwrecks, vessels suffering a high fatality rate from disease were relatively rare on the Australian route from the 1840s. Nevertheless, high mortality on ships that suffered epidemics …[and] … The tendency to extrapolate from these, and from the tragic passages of the Atlantic ‘coffin ships’ of the late 1840s, has created a picture of nineteenth century emigrant voyages as a calamity of universally tragic proportions. The suffering on the fever ships was truly appalling in an era when the … transmission of cholera and other infectious diseases were not yet understood. Yet from the beginning of government-assisted emigration to Australia in 1831, humanitarian concern was widespread, leading to tighter regulations governed by the Passenger Acts.” 3

George and Ann Gray on the ‘Thomas Arbuthnot’

George Gray was both a stonemason and builder, he had a wife and 4 children and along with his brother in law Edmund Bull and his family already in the colony, he had a place to go where he could work for a magistrate, so someone with influence in the colony. the journey out though proved to be difficult for the Gray family.

Death of James Gray and his mother Ann Gray

The ‘Thomas Arbuthonot’ was only 6 weeks out of England when baby James became ill, he died on the 18 November, 1848. The Surgeon Superintendent’s (Ship’s Doctor) report on arrival states; ‘Died of infantile disease not infectious.’

It is interesting that Caroline Chisholm, the well known humanitarian working for the improvement of women and children’s welfare, noted in her evidence to the Select Committee on Emigrant Ships in the House of Lords in 1854, that ‘mother’s milk generally fails them at six weeks’. Caroline Chisholm ran the Family Colonisation Loan Society operating her private emigration scheme, so was well placed to argue for the improvement of conditions especially for babies, children, women and families.

Ventilation was poor on these ships along with overcrowding and if there was contaminated water, it could cause sustained difficult to treat and cure, diarrhoea.

Children and babies nutritional needs were not usually taken into account within the provisions on ships as children’s passage was often not paid for, their needs were not always addressed. All these things contributed towards the difficult conditions for those onboard.

The Surgeon Superintendent for this voyage of the Thames Arbuthnot, was Mr D Roach. The ships master was Captain G Heaton, who also was the Master for the next voyage arriving in Sydney in 1850. It is difficult to find information about Dr Roach but we can get an insight into voyaging on the Thomas Arbuthnot from the next surgeon-superintendent Dr Charles Edward Strutt, an English doctor whose journals have been preserved from the 1850’s voyage. He was appointed by the Colonial Land and Immigration Commissioners for the voyage of the Thomas Arbuthnot to Sydney arriving in 1850. He was known as an ‘exceptionally humane and compassionate superintendent’

Notes relating to the ‘Thomas Arbuthnot’ 1849/1850 voyage to Sydney;

“Dr Strutt was obliged to sort out the usual grievances, to oversee the meals, and to attend to the sick. ‘Indeed’, reported the press, ‘a well ordered and well-conditioned ship combines the discipline of a camp with the regularity of a private family’. During the evening lanterns were hung on deck for music and dancing, and on Sundays church services were held, in different parts of the ship, for Protestants and Catholics. As usual washing was done on deck twice each week, and every three or four weeks the boxes were brought up from the hold to exchange worn clothing for new.” 4

The need to care for four children including a young baby, alongside Ann Gray’s failing health, would have made her capacity to cope extremely difficult. The report by Dr Roach on arrival in Australia on the death of Ann Gray, aged 27 years states; ‘died of consumption 15th December‘ (1848) Another source adds with quotes from the microfiche records; ‘Deaths on the voyage; Gray James H.E. Inf. 18 November 1848 Diarrhoea.‘

The ‘Thomas Arbuthnot’ was a fast ship for its time and on Thursday 18 January 1849 the Sydney Morning Herald report of the voyage states;

“The Thomas Arbuthnot made a good passage of one hundred and one days from Plymouth. She has on hoard 260 immigrants, principally English, of whom 47 are married couples, 43 single men, 42 single women, 44 boys, and 28 girls from one to fourteen years of age, and 10 infants. Six deaths and three births occurred during the voyage, of the former three were of infantine disease, one adult of fever, one of consumption, and the other a boy of about twelve years of age, who fell overboard and was drowned, although a boat was lowered and everything done that possibly could be to save him. The emigrants on board are all in good health, and credit is due to the captain and surgeon for the orderly and cleanly state in which the vessel appears to have been kept, On the 24th October the Thomas Arbuthnot signalled the ship Derwent, off Cape de Verde Islands, eight weeks out from Plymouth, bound for Adelaide with emigrants.” 5

Whilst this newspaper report on the voyage indicated the voyage was generally a credit, Dr Strutt the next surgeon-superintendent did see some need for improvement of conditions onboard. He ordered; ‘improvements in the ventilation system and began the daily scouring of the ship from top to bottom’ but noted that the married quarters were not always kept clean by the passengers. Reference of this would include the keeping of nappies clean and being watchful of children not toilet trained. Unfortunately we will never know if this would have made any difference but it was too late for baby James and his mother Ann.

George Abner Gray, Ann’s and George’s third child wrote a journal in later life and recalls his mother’s experience on the voyage over. Like most memories there are a few details astray and as he was only 2 years old they are likely to be memories from his father, but it is still valuable to hear directly from him;

“My mother having to brake up a comfortable home and leave all dear relations behind, played on her constitution and she never called but sunk lower as we got on the seas, although the daughter of a sea captain, she could not encounter the hardships of the voyge. The living on board ship in those days was not good, so different to what she had been acustom to that she graduly got worse to worse, a sickness broke out on born among the children and my youngest brother died a few weeks after my dear mother died and were committed to the deep. I was given up by the Doctor and he said I could not possibly recover, but I am still alive!!” 6

Whilst we have no information on why George and Ann Gray along with their four children sought to come to Australia, we get an insight from Doctors at Sea : Emigrant Voyages to Colonial Australia by Robin Haines;

‘Yet another unmeasurable aspect of the emigrants’ collective profile as ‘select lives’ is that, no matter how poor, they may have been more adventurous than their more timid peers who stayed at home. Their letters and diaries pulsate with determination to find a life in an agrarian economy where their rural skills were in demand, and where their dream of a patch of soil of their own was within their grasp. Others sought attainable goals such as a judicious marriage, an upwardly mobile position in the building trades, or in baking, brewing, or milling, or other burgeoning industries springing up in the new towns on Australia’s coasts and hinterlands. In that sense, assisted emigrants who boarded ships bound for the Antipodes in the nineteenth century (representing well over half of all emigrants in each colony but Victoria whose armies of incoming gold seekers swamped the 166,000 assisted emigrants arriving in or near Melbourne), were unrepresentative of the less adventurous friends and relations they left behind.‘ 7

From the collections of the State Library of New South Wales [a928398 ML 374]

References

- Haines, R.. Doctors at Sea : Emigrant Voyages to Colonial Australia, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2005

- Haines, R.. Doctors at Sea : Emigrant Voyages to Colonial Australia, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2005

- Haines, R.. Doctors at Sea : Emigrant Voyages to Colonial Australia, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2005

- Haines, R.. Doctors at Sea : Emigrant Voyages to Colonial Australia, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2005

- Haines, R.. Doctors at Sea : Emigrant Voyages to Colonial Australia, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2005

- Haines, R.. Doctors at Sea : Emigrant Voyages to Colonial Australia, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2005

- Haines, R.. Doctors at Sea : Emigrant Voyages to Colonial Australia, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2005